Dada history

BRIEF HISTORY OF DADA

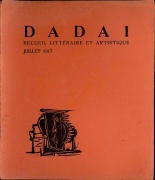

An artistic but initially literary movement, founded in 1915 in a spirit of rebellion and disillusionment during World War I and lasting until about 1922. Although the movement had a fairly short life and was concentrated in only a few centers (New York being the only non-European one), Dada became highly influential, causing a sea change in art history, allowing for new and more modern art movements to question and challenge traditional artistic and cultural conventions and values; indeed this was its aim. The intention of Dada art – often called anti-art – was to expose the ridiculous pretensions of a society that countenanced World War I by producing social commentary in the forms of creatively nihilistic and antirational art; for example, Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917; Paris), a ceramic urinal signed R Mutt (the US manufacturer).

European Dada was founded at Cabaret Voltaire in Zürich by a group of performers, writers and artists headed by the German musician and poet Hugo Ball, his wife Emmy Hennings and Richard Heulsenbeck along with the French sculptor Jean Arp and the Romanian poet Tristan Tzara. There are several accounts of how the name Dada (French for hobby horse) originated but evidence points to the word being chosen at random by Hugo Ball placing a finger on a random page of a French encyclopedia opened by Richard Heulsenbeck as a way of finding an alternative name for a Swiss singer booked in to the Cabaret Voltaire. When she didn’t show up and the name was put to the small group, it was enthusiastically taken up as a focus for their protest art activities and later became Dada’ism by being promoted as a distinct art / anti-art movement by Tzara.

During the war many intellectuals took refuge in Switzerland (which remained neutral throughout the conflict) and it consequently had a lively artistic life. The center of Dada activities in Zürich was, as mentioned, the Cabaret Voltaire, a club founded in 1916 by Hugo Ball. Typical events there included the recitation of nonsense poems, sometimes several at the same time and accompanied by raucous music, as well as other performance art. Unruly behaviour caused locals to complain and the club was forced to close in 1917.

From Switzerland Dada spread to Germany towards the end of the war, flourishing mainly in Berlin, Cologne, and Hanover. In Berlin Dada was strongly political, the leading figures including Raoul Hausmann and John Heartfield, two of the great pioneers of photomontage, which they used to attack militarism and nationalism. In Cologne the leading figure was Max Ernst, who organized a Dada exhibition at which hatchets were provided for visitors to smash the works on show. In Hanover Kurt Schwitters created a novel version of collage using everyday refuse.

Although there were Dada groups in a few other European cities, outside Germany and Switzerland, some the most important activities of the movement were in New York where three major artists became involved: Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Francis Picabia. Duchamp, the most original of these, was the first to adopt the name Dada from Ball, and Picabia was the most vigorous in promoting Dada ideas. He subsequently traveled a great deal and helped introduce Dada to Barcelona and Paris. In Paris Dada was one of the sources of surrealism, officially launched in 1924. Several artists (including Picabia) participated in both movements. The two movements shared an antirationalist outlook, but while Tzara’s Dada, contrary to its essentially moralistic definition by Huelsenbeck, was seen as nihilistic (believing in nothing, or denying all reality), surrealism was more positive in spirit.

© Research Machines plc 2005. All rights reserved. Helicon Publishing is a division of Research Machines plc.